The Lifecycle of a central line can be broken down into 2 broad subcategories: Insertion, and Care and Maintenance. Much has been made of the role that adhering to proper sterile technique has played in reducing CLABSI, but far quieter has been the cry for improving the skill of the inserters. If you want to change your results, you will need to change your process. And if too many of your CVCs are becoming infected, a change in the process means a change in how they’re inserted and how they’re maintained. Though it only takes about 30 minutes to place a central line, the average central line in the US remains in place for 6 days. So while the insertion phase of the central line Lifecycle gets most of the attention, the Care and Maintenance phase represents the majority of the Lifecycle of the line.

Insertion training

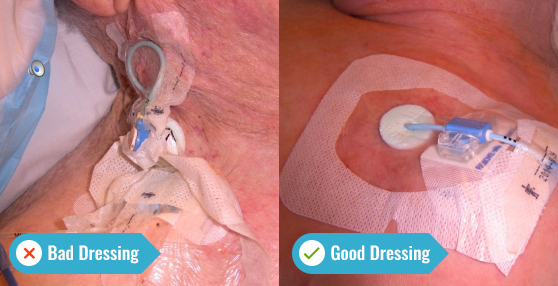

There’s an unfortunate reality when it comes to formal training for CVC insertions: it’s essentially non-existent. Most physicians learn the procedure during their residency, and the clinical guidance is minimal. The combination of scant training, outdated practices, and lack of standardization lead to bad outcomes. Furthermore, few physicians have their skills updated as new technologies emerge. Our definition of a proper insertion goes beyond just adhering to the Central Line Checklist, and while the prevalence of Ultrasound Guidance (USG) has allowed clinicians to visualize veins, very few have learned how to puncture the Axillary vein using USG. Insertions in the delto-pectoral grove, as pictured above, leave the catheter in a flatter area to keep the dressing intact. An intact dressing is critical to preventing infections. This is what we mean by thinking about the entire Lifecycle of a CVC.